Tales From a Past Life

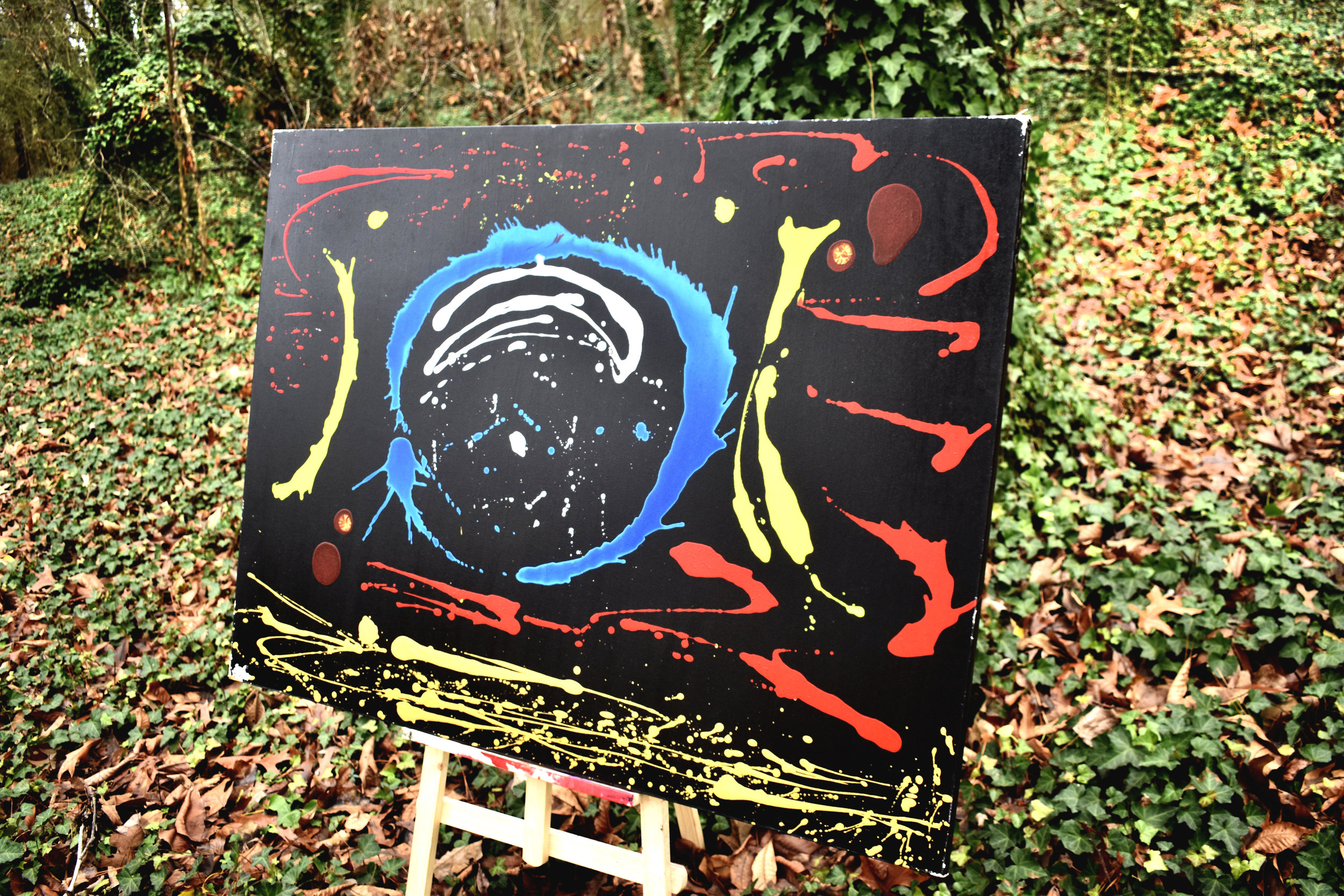

Featured Artist: Derrick Mckenzie Jr, acryllic, 36x48 canvas size, Micah Briggs Collection

“‘War Cry’ is a visual expression of what victory, bravery, courage and self-worth look and feel like. A representation of finally getting to a point where there is no room of doubt, stress or disappointment. It’s stepping up to the challenge, giving the divinity Himself a loud, warrior-like war cry…it’s being a conqueror.”

“Basically he didn’t eat unless I fed him. He slept a whole lot randomly. He was really skinny and I feel like now, looking back, I could tell when he was high. Because his voice was very different…hoarse, maybe.”

“That was just the downer part of it. Because I was more into downers. At the end, for probably like the last year, I was doing heroin and cocaine together.”

“Yeah. ‘Speedballs’. Cocaine raises your heart rate and then heroin lowers your heart rate. So it balances out.”

“With [speedballs] you could be a functioning addict.”

I followed Morgan up the stairs to her two-bedroom apartment. They’ve only lived there for a few months. She wore an over-sized Nirvana sweatshirt, with leggings and combat boots, and carried with her a bag of groceries.

The first thing I noticed when we walked in was the matching throw pillows—both geometrically patterned—that decorated the navy blue couch. Then the coffee table, the rug and decorative “C” and “M” that hung on the wall behind the couch. Everything coordinated perfectly. A fall-scented Bath and Body Works candle burned on the kitchen counter and filled the room with a warm, sweet aroma. And while there were baby toys all around, nothing felt out of place or messy.

Then I saw Morgan’s husband. “Hey, Clint!” “What’s up.” He was washing dishes and putting away the groceries. As a competing body builder, he towered over Morgan’s petite, 4’10” frame. They were nothing less than comfortable around each other. And nothing about their cozy home in that two-bedroom apartment suggested anything about their past.

There were no apparent remnants of the person Clint had once been.

“I was a good liar. I was a very good liar…I would say the withdrawals [were the cause]. Coming off [the high] and then just trying to find a way to get it—get back in that state of mind. I’m not a thief, but I would definitely steal to get more.”

I was pleasantly surprised by Clint and Morgan’s transparency and willingness to tell his story. He jumped right in explaining who he had been in a past life. The chronic lying, explosive temper, sleeping on the streets and shooting up in the McDonald’s bathroom. I wondered aloud what force could possibly be powerful enough to drive not just him but all addicts to engage in such reckless behavior. Morgan chimed in: “It was the withdrawals.”

Withdrawals. A relentless, debilitating hell wrought upon the minds and bodies of drug addicts and alcoholics who dare to try to kick their bad habits. Imagine the brain as a spring being pushed down by drugs and alcohol. These substances work to suppress your brain’s natural production of neurotransmitters like serotonin, dopamine and noradrenaline.

When the substances suddenly disappear, the weight on the spring is released. The brain rebounds full force and the production of neurotransmitters kicks into overdrive, releasing a surge of adrenaline that causes withdrawal symptoms. And the longer and more severe the addiction, the heavier the weight on the spring. The more energy that spring has to release once the weight is lifted, the more intense and painful the withdrawal.

Clint didn’t have to dig very deep to find fresh memories of what it was like to come down. “I could feel my joints getting bad…everything just starts shutting down.” Aching body. Heightened anxiety that led to panic attacks. Fatigue. Runny nose and flu-like symptoms. Morgan recalled an old friend of theirs who’d also struggled with addiction: “You know, when Tommy said he was going through withdrawals he was throwing up blood.”

Symptoms can range from anxiety, depression and insomnia to heart attacks, hallucinations and grand mal seizures. Still, Clint insists quitting cold turkey is the best choice, as opposed to being weaned off with prescription drugs like Suboxone and Paxil. “You’re basically just swapping an illegal drug for a legal drug, because you get high off it. Especially if you take a little bit more than what’s prescribed.”

Hearing, in vivid detail, about the horrors that lie on the road to recovery was harrowing. But I wanted more. He wasn’t born an addict and his disease didn’t just appear out of nowhere. I wanted to go back to the beginning and walk with him through his memory from the start of his journey to where he is today.

“Take me down that road,” I said. So he did.

“So where are you from?”

“Blount County. I grew up there. [Morgan and I] grew up in the same town.”

26-year-old Clinton Bailey was born and raised in Blountsville, Alabama. While it may only be an hour’s drive away from the cultural hub of Birmingham, the two worlds couldn’t be more different. If you’ve never had the pleasure of experiencing rural Alabama, it’s fine. It doesn’t take much imagination to picture it.

“Republican. Bible Belt. Uncultured. Poor.” Morgan certainly had no qualms releasing a string of adjectives to describe the world of their youth. Picture wide, sprawling fields of wheat, corn and cotton that stretch far beyond the horizon. Christian churches of varying denominations on every corner. A nearly all-white population, baked-in poverty and seemingly endless trends of drug abuse.

Meth might be the most popular substance amount Blount County residents but there’s still plenty of variety to go around. “[Doing drugs] makes you feel bigger than you are,” explains Clint. “It gives you a sense of purpose.” In a world where urban living, higher education, interracial relations and liberated mindsets are taking mainstream American culture by storm, the couple describes Blount County as impervious to change. A forgotten-about pocket of society that will forever be stuck in time.

The majority of the locals there are perfectly content with marrying young, sticking to what they know and leading a simple life far away from the big city. And despite Clint’s desire to break away and experience more, he describes his mother as being perfectly content living a Blountsville lifestyle. “That’s why my mom and dad didn’t work out. It’s cause my dad’s got my mindset of ‘I want to see things, I want to get out of this small town. I want to experience things.’ My mom and my brother, they just want to stay [there]…”

He paused for a moment and thought back on the years leading up to his parents’ divorce, which closed the book on 25 years of marriage when Clint was just 15. Although he was well taken care of—doted on, even—he never had the luxury of being shielded from the reality of his parents’ problems growing up. In place of bedtime stories, his childhood was filled with tales of his father’s many extramarital affairs during his time in the military. In fact, Clint’s mother saw no reason to hide the truth of his dad’s constant cheating and the effect it all had on her.

But children aren’t mentally or emotionally equipped to deal with that level of stress. They instinctively take on their parents’ woes as their own before setting forth to rectify problems that aren’t their responsibility under circumstances they can’t control. Over the years, helplessness and desperation took root within Clint as the pillars of his home began to crumble. His parents’ marriage was over. And like any young boy his age would’ve done, he blamed himself.

“I always tried to fix [my parents’ relationship] but in reality, there was no fixing it. So subconsciously I always thought of it being my fault. And I tried to stuff my subconscious down with drugs or alcohol so I wouldn’t have to deal with what was going on in my head.”

If any of us are to live a decent life we have to forge our own path. But we risk getting lost along the way.

Driven by a desire to be independent—or perhaps a fear of being at the mercy of someone else—Clint left home at the age of 17 and moved to Cullman, Alabama in the nearby Walker County. Selling weed helped him keep food on the table, while smoking it helped take the edge off. Over time, marijuana evolved into lortabs and oxycontin. He’d already become familiar with the pain killers after a biking accident broke his back in his early teens. And like most drug addicts in the beginning, he thought he had his habit under control.

80 percent of heroin users point to prescription drug abuse as their starting point, though. With statistics like that staring you in the face, that sense of control is quickly revealed to be nothing more than an illusion. Even when he started shooting up—something he swore he’d never do—he justified his actions. After all, the needle produced a quicker, longer lasting high than snorting did and it was cheaper. So really he was saving money.

“They manipulate themselves more than they manipulate other people,” says Morgan. She seems to have made peace with who her husband was in the past and when she brings up old memories, it’s as if she’s speaking of a different person entirely. “He was so quick to make excuses when he was on drugs. He was always going to ‘have lunch with dad’ or would just be MIA for a few hours at a time.”

Surrounded by toxic relationships and an enabling mother, Clint’s behavior went from bad to worse as his addiction gradually spiraled out of control. Run-ins with the law, brief stints in jail and a habit of burning bridges eventually became a lifestyle as he grew from getting high for fun to needing drugs to survive.

Humans are creatures of habit, so aside from the chemical and physiological dependence, drug addicts and alcoholics are hopelessly addicted to the routine. No matter how self-destructive and catastrophic his path became Clint stayed the course, regardless of any warning signs that were thrown his way.

At the age of 18 during one of his stays at the local jail, he shared a cell with an inmate more than three times his age. The man, with his gray hair and skin worn with age and hard luck, had used up all of his chances. He would never see the light of day again. One day he turned to face the teenager in his cell. “Do you want to be here when you’re my age?” While he was too young and arrogant to heed the advice at the time, Clint remembers those words as a pivotal moment in his life.

But his journey was far from over and the worst was yet to come.

“You have to choose for yourself to get better. And until you exhaust all your crutches, there’s almost no coming out of it.”

Nighttime had fallen on the city of Birmingham as Clint emerged from his dealer’s house, heroin freshly coursing through his veins. The deadly combination of driving while high didn’t concern him too much as he hopped behind the wheel and headed back home to Blount County.

On that long, dark drive out to the middle of nowhere, he came face to face with what he describes as “one of the scariest things I’ve ever experienced.” Out of the darkness on the road ahead appeared the menacing face of what he described as a devil, whose eyes twinkled with malice as they stared at him through the window. He blinked. It was gone. Unsure if what he saw was real or just a hallucination, he drove on. He couldn’t shake the feeling, however, that his demons were catching up to him.

It took a few years but eventually, everything in Clint’s life came to a head. After a heated argument with his mom led to her kicking him out of the house and calling the police, he found himself on the streets again. Except this time, he was on the run and wasn’t likely to get away. He raked through every contact in his phone and called everyone he knew, including Morgan, looking for a place to stay the night. No luck. All those bridges had been burned. So he ran.

Down the street, in and out of neighborhoods and deep into the woods. He dodged the police for hours as he weaved through the thick brush of Alabama’s back country and hid in the shadows. After things cooled off he wound up on his brother’s doorstep strung out, soaking wet and completely exhausted. After some deliberation, his brother let him in and Clint breathed a sigh of relief. Finally. A safe haven. Or so he thought.

About an hour after he arrived, a loud knock at the door seemed to shake the whole house. It was the police and they had the place surrounded. It was over. One of the arresting officers recognized Clint as someone he went to high school with. Disappointment painted his face.

“Clint, man, what are you doing?”

“It’s the drugs, man. They got a hold of me.”

After spending a few days in jail, the judge told Clint he had two days to go to the rehab or else prison would be his next and final stop. And in an unusual turn of events, they let him go. With no friends to call, no car and no money, he wandered off aimlessly down the road. He soon found himself stranded at a gas station and too tired to go on. By some stroke of luck and a little bit of chance, he crossed paths with one charitable stranger after another.

Two hitchhiked rides later he stood in front of his uncle, the one relationship he hadn’t destroyed. “I was tired. Tired of it all,” he recalls. In an effort to get him off the streets and back on his feet, his uncle loaned him some clothes and let Clint stay at his late grandmother’s vacant home just up the road.

Upon arriving to the old house, Clint came across something his uncle had clearly overlooked: a refrigerator full of beer. He helped himself to one. Then another. And another. “By the time my uncle showed up the next morning I was still going wide open.” A nasty argument over the empty bottles and slurred words ensued before the two hopped in the car and drove toward Birmingham. Clint was headed to the Jimmie Hale Mission, a local rehabilitation center known for changing lives.

But they were overbooked and had no room for another resident, so they offered a few days of overnight stay instead. Good enough, but Clint still had a few hours to kill before he had to be back to check in for the night. So in the meantime, he managed to pawn some jewelry he’d stolen from his grandmother’s house, call his dealer from a stranger’s phone and buy enough heroin and cocaine take the edge off the stress of the past few days.

On the way back to downtown, he was still shooting up in the passenger’s seat of his dealer’s car when he began slipping in and out of consciousness. Once downtown he stumbled out of the car and took just a few step before collapsing on the sidewalk. His dealer drove off. “Two punk skater kids found him and brought him into a restaurant, then called an ambulance,” said Morgan. Clint’s heart had stopped beating. He was legally dead.

Once in the ambulance, two doses of narcan jolted him back to life. Unlike so many others before him, he’d been given a second chance. After getting released from the hospital he spent 11 months recovering at the Mission with Morgan by his side. In September of 2017 he and Morgan welcomed a healthy baby girl and the next summer, finally said “I do.”

Today, those tales of a past life are nothing more than distant memories. But the numbers are still very real. Heroin usage among adults aged 18 to 25 has doubled in the past ten years and relapse rates currently sit between 40 and 60 percent. Even more daunting, only 10.9 percent of individuals who needed treatment for substance abuse in 2013 actually got it. In that same year over 95 percent of those who needed treatment and didn’t receive actually believed they didn’t need it. However happy his ending (or new beginning), Clint’s triumphant comeback was not and is not the norm.

Maintaining sobriety is no easy feat. To Morgan, it’s obvious how hard her husband works to keep his head above water. “Now he can’t sit still because he always has to stay busy until he’s so physically tired that he can’t sleep,” she explains. “It’s like he needs constant distraction. He says he doesn’t think about it anymore but that’s because he’s not letting himself have the chance to think about it.”

It’s likely that, for the rest of his life, Clint will have to be hyper-aware of the reality that ghosts of addictions past are very real. But for now, who he is takes precedence over who he was. And from the looks of it, who he is is here to stay.

UPDATE: Clint relapsed in 2020. He and Morgan are now divorced.

“When people are ready to, they change. They never do it before then, and sometimes they die before they get around to it. You can’t make them change if they don’t want to, just like when they do want to, you can’t stop them.”