The Missing link

Photography courtesy of Issac Nunn, creator of Suburban Creative.

“To live without reflection for so long might make you wonder if you even truly exist.”

Photography courtesy of Issac Nunn, creator of Suburban Creative.

“To live without reflection for so long might make you wonder if you even truly exist.”

Simply because my mother is Black and Black women are 243% more likely to die during childbirth than White women. But if you asking me when I experienced racism, I can give you story after story.

I can tell you the time me and my friends got pulled over late at night on campus. The officer asked for my license and registration. Everything checked out. He then came back to the car and asked for everyone’s student ID because [apparently] we all had to be students to drive through a public road. Also, [I could tell you] how astonished he was that we were able to produce them.

Or I can tell you about when I was pulled over in my new car riding through Vestavia Hills because I hadn’t gotten a chance to purchase my tag yet. Officer pulled me over, asked when I got the car. I told him yesterday and showed him my title and the paperwork necessary. However, he had to call a second cop because I might be up to something since the car was registered in my mother’s name. Whose name is almost identical to mine.

I could tell you my experiences in academia. When I turned in a paper freshman year on the Tuskegee Syphilis experiment. The TA said that it was too biased. That saying the ‘experiment ensured the Black community could not always trust the government’ was an extremist take.

I could talk about how every day in law school, I watch White classmates who shouldn’t have graduated high school stumble their way through the semester to get by. Meanwhile, I get told all the time ‘it seems like you don’t care’.... Oh really? But the girl with the purple hair, or the dude who never shows up, or the person in the corner asleep.... they care right? It’s a surprise my grades are better than the majority, huh?

I could talk about how I was watching Kobe’s last game and security came to the door with guns and bullet proof vests because it ‘sounded like someone was being killed’. And for some reason a noise complaint drew enough caution to bring riot gear. Or how my Karen-ass apartment manager thought she could ‘shhh’ me in the middle of a sentence. Then pretended to be threatened when I reminded her that I’m a grown ass man.

I could talk about systemic racism. How, statistically, it’s going to be harder for me to get a job after graduation than my mediocre White classmates.

I could tell you about how the schools I attended when I was younger were always underfunded.

I could talk about the economic pressures graduate programs put on applicants so that it disadvantages them from applying and getting in.

I can tell you how I’m always over-policed and never served. No matter if it’s at a restaurant or at work.

I could tell you no matter how smart I am or what I accomplish, people always see ‘nigga’ first and ‘person’ last.

But those will bore you more than the other stories. So these are my very small, tiny anecdotes about racism. I got stories for a few lifetimes. But I don’t have a lifetime to explain. I got shit to do.”

—Varian Shaw

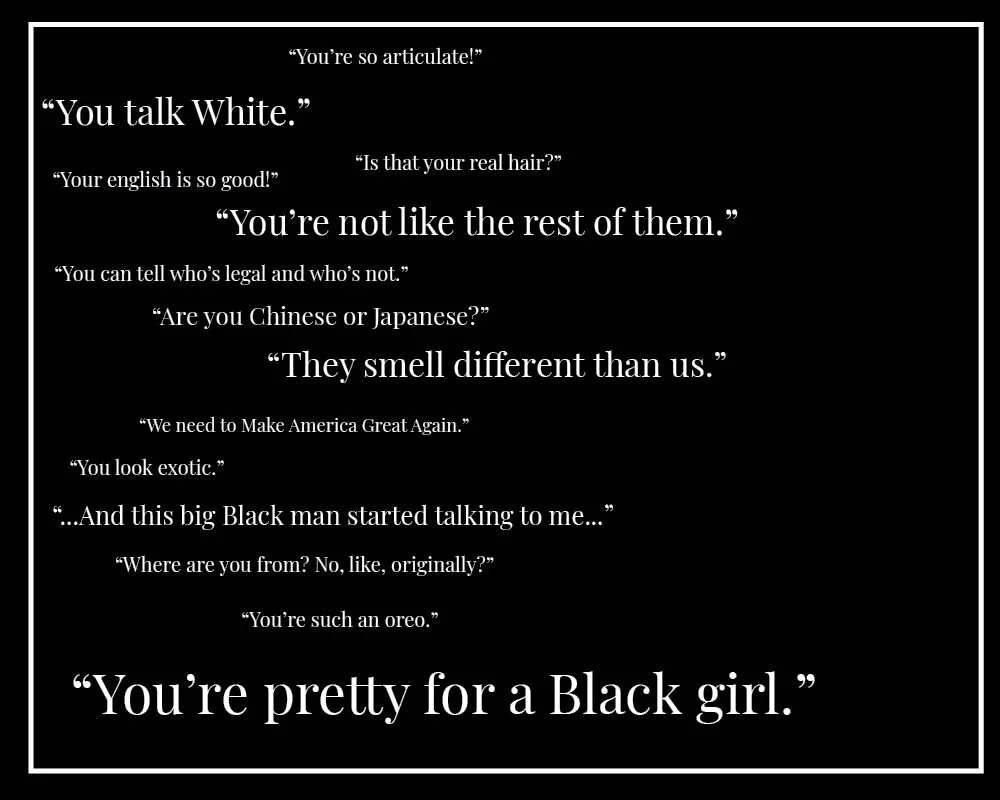

a microaggression is

a term used for brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral, or environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative prejudicial slights and insults toward any group, particularly culturally marginalized groups. Source.

and how it affected my biracial brother. There was a dollar store we would always stop at on the way home from school. My mama would give me some cash and send me in to get a few essentials. One day my little brother, Chris, had some money to spend.

While I was still taking mom’s inventory, he ran in ahead of me. When I entered the store, the cashier was aggressively telling him he needed to put his book bag behind the counter. I was worried instantly because I saw this cashier all the time and she never asked me to place my bag behind the counter. I thought she was planning to steal from Chris, so I told him not to do it.

I confronted her and called her out for never asking me to put my bag behind the counter. I had no idea what was really going on and that she never asked me to because I was White. We did our shopping, she rang us both up, but the story wasn’t over. We got in the van and told Mama what happened. She took me with her back into the store and, as she was yelling at the cashier and demanding a manager, I learned that Chris had been ‘racially profiled’ as we call it now.

Mama got the woman fired, but it was a wake up call. Mama would tell Chris not to put his hands in his pockets when we were out shopping, never telling me not to. She took away his BB guns and squirt guns that looked ‘too real’ after a kid at our park was surrounded and almost shot by police for having a black BB gun because someone called 911 and said it was real. When we got older, Mom and Dad would tell Chris how to interact with police officers if he ever got pulled over, but never told me how to be careful if I was. It was clear from early on that I lived in a safer bubble than my brother did. That he had to operate differently even before he understood why.

Everything after that moment seemed to compound and crush me.

We tried out a new church at the behest of my Dad, and the old White parishioners would snicker and ask each other where the ‘nigger boy’ came from. Our younger sister, who was born after Chris, was only referred to as the ‘White nigger’ by our racist relatives because she was conceived after our mother’s womb was ‘contaminated’.

Kids would tease us and ask if my brother was adopted. As we got older, people would tell us what a ‘cute couple’ we were with fake smiles that betrayed their true thoughts. Their eyes would get even angrier and their fake smiles would drop completely when we told them we were siblings. In high school, some of the other White kids would suddenly stop talking to me when they found out my brother was Black and wasn’t adopted.

This is not a comprehensive list.

The isolation and injustice I felt and still feel will never compare to that of my brother’s experiences. Living in a world where I can’t shoulder my brother’s burdens and can’t fully relate to him is a torture I wouldn’t wish on anyone.”

—Delora Von Hoeft

I was eleven years old and alone on an elevator. A White man of a certain age—nearly a ghost—stood [in front of the door] with his arm extended in front of his wife. I froze.

A decade would pass before I would meet another spirit like his.

It was just after dusk in the small town of Maplesville, Alabama. Blue lights began to bounce around the interior of my car as I was making my way back to Selma. I pulled my black Pontiac Sunfire to the side of the road and grabbed my registration and proof of insurance from the glove box before lowering my window about halfway. A pale White man of a certain age—shining a light in my eye—came alongside me. He stared into the darkness ahead of us and then in the opposite direction before he finally asked, ‘Boy, do you know why I stopped you?’

‘No, sir,’ I responded. Frozen again. Recalling Orlando.

I pressed that elevator button with urgency, forgetting that it takes an eternity for elevators to reach the lobby even if only from the fourth floor. And it takes twice as long if you were a kid with a janky attention span. All I could think about was the passive aggressive comments my stepmother had just made to my dad because I wanted to get my digital camera from our hotel room. I did not let the doors open completely before rushing in—smashing the ‘4’ several times to force the doors shut again. The elevator stopped on the third floor. When it opened, I watched this creature of a man’s face turn stark white when he laid eyes on my blackness. His wife barely noticed me and tried to step on the elevator. He blocked her path with his arm.

‘We aren’t riding with this nigger,’ he said to her gently.

The elevator closed. I rode it up to the seventh floor before I was able to think. I never told my dad or stepmother about what he said. I knew what it meant because of what it felt like. It chilled me. Just as being called ‘Boy’ by that officer chilled me.

‘Your tag light is out. Where are you headed, boy,’ the office asked as she pointed his flashlight at my backseat.

‘I’m a student at the University of Montevallo and I’m heading to Selma to visit my dad,’ I told the officer, wishing that another car would drive by us to disrupt the dark.

‘Get that fixed,’ he said abruptly.

He walked away. And I felt like I had been passed over. Like that backroad was Egyptland and there was lamb’s blood around the frame of my car door. So I drove home. Haunted.”

—Ben Jackson

I remember when the Klan would gather at the intersection down the street from my house. That must have been about 1980. I didn't understand why those men were dressed up like ghosts and why my mother was begging my dad not to say anything to them (she was rightfully scared that they would retaliate against my liberal, hippie parents).

Going to school in the same neighborhood, I was the only kid in school who didn't use the n-word. My best friend in elementary school admitted to me in secrecy that her dad had been a member of the KKK, ‘but they didn't go after all Black people, just bad people like wife beaters and stuff.’ Years later, when we were teenagers, that same friend referred to a dirty house as ‘dirty like a nigger's house.’ I was shocked but I didn't say anything. I'm still ashamed about that.

Also, my grandparents lived in Forestdale, which was once a White suburb of Birmingham. Over the years as Black families moved in, most of the White people fled. By the 1990s, it was just a handful of old White people, like my grandparents, and [mostly] Black people living there. The Black man a few doors over ended up being my grandfather's best friend and I got to know him well. However, it struck me as the height of irony when he grumbled about how the neighborhood was a bad place to buy a house these days because it was ‘going Hispanic’.

They became friends only in older age and I think they cared for each other deeply and kept an eye on one another after they were widowed. However, my brother and I heard them occasionally refer to each other—laughing and in front of each other—as ‘my nigger’ and ‘my honky’. My grandfather was generally progressive and this was the only time I ever heard him use that word. My mom said when she was little he called Black people ‘colored’, the polite term back then.

Anyway, it blew my mind that he'd say that to his friend's face and that they both seemed to think it was funny. All this to say the obvious: race relations are complicated and sometimes, so is racism.”

—Anonymous

but it’s the earliest one I can remember that really affected me (I am White). My sister had recently started college and I was in middle school. She was cheer captain and had been dating the quarterback at her university long enough to bring him to my grandparents’ house for Thanksgiving. From my perspective, everything went well. He was funny and charming and outgoing. My parents liked him. I liked him.

My sister told me later that night that my grandma had pulled her aside after dinner. She took her to my dad’s old bedroom to talk about something serious. There, my grandma told my sister that her boyfriend was great—kind, funny, handsome—but that he was ‘too dark’ for her. His family was from Mexico.

Before that, I’d thought racism was a thing of movies. Of stories. That only obviously hateful people could be racist. But it was my own grandmother. And she was trying her best to pass that on to my sister…It definitely taught me about racism toward Black people too. I realized that my grandma saw it as a literal spectrum. The lighter the better, the darker the worse.”

—Madison Griggs

but it's not.

To be honest, I'm only just beginning to realize and understand the magnitude of what I went through and was taught as a kid. People post the meme about that White woman with the picket sign [that reads] ‘Sorry I was late, I had a lot to learn,’ but that lady is me, too. Even I, a Black person, had to wake up and accept what has been happening in front of my face my whole life from the [perspective of the] Black narrative.

The most detrimental things that happened to me were not at the hands of White people, but Black. Having someone that looks like me spew hate is worse than anything any White person has done to me thus far. The self-hate I had for myself and the fear of speaking out prevented me from fighting for my own people.

It took me a long time to identify with affects of racism, colorism and prejudice as my story too. Colorism is not always out loud in the open, but justified behind closed doors in the comments and actions of others.

I was bullied from the fifth grade until graduation mostly by Black people. They teased about my skin color often, and my voice. I was ‘too dark’, ‘left out in the sun’, ‘fugly' with big lips; a freak. My voice sounded ‘White’. In the sixth grade onward, I embraced rock music as an escape and had White and Hispanic friends. I was ‘wanna-be White’, ‘dark White’, an ‘Oreo' or not ‘Black, Black’.

Even my family said these things. When I went natural in the 12th grade, I ‘looked like a slave with Dick-Sucking Lips’. Because the black people openly teased me, the White kids called me these things too.

One of the most humiliating experiences of my life happened at a fifth grade zoo trip. When we got to the primate exhibit, this group of kids (Black) pointed to the gorilla cage and said out loud 'look Briana there goes your family!’ All the kids (White and Black) started laughing and pointing to different primate species as my cousin, uncle, etc.

I know that's where my identity crisis began. I hated my dark skin color and myself. I felt worthless and ugly. That experience really tore me down. I completely lost my self esteem. I tried to make myself small and invisible. I didn't want to be Black anymore. If I was lighter, I would be treated better and be richer. Even some of my family members would make plenty of colorist comments about my sister being prettier than me because of her light skin and longer hair. She got more attention and I felt looked over, like an ugly duckling. By everyone, everywhere.

Eventually, I got new friends that were non-Black who didn't care about the color of my skin. I felt embraced for once. I wore as much black as my conservative Black family would allow and could care less about Black culture. I wanted to be NOTHING like my family. Honestly, it wasn't that hard to do. I went to a mostly White school with mostly White teachers K-12. Everything I learned about Black history was the same safe, standard ‘MLK marched, Rosa parks sat’ boring stories in the Black history section.

I was so brainwashed by the whitewashing of our history that I actually did not care about it. Why would I, they didn't? At one point I even considered buying myself a rebel flag necklace because it looked cool. Thank God I spared myself from the cringe later on in life!

One day, when I was about 10, my mom broke down crying because I said, ‘I don't care about slavery that was 200 years ago, they don't do that any more. You need to stop living in the past. White people and black people get along now who cares…' I truly could not understand her reaction until a couple of years ago.

I could go on and on in ad nauseam about every account. I could write a five-inch-thick book. It took counseling and going to college with people like me to understand that I was beautiful. To look in the mirror and not judge my face by my features or hair. To proudly embrace my culture as a Black person that is different from the norm.”

—Briana Brown

colorism is…

“prejudicial or preferential treatment of same-race people based solely on their color.”

“These voices and perspectives—our voices, our perspectives—are key to harvesting the many opportunities alive within American democracy. But our nation must do the work of drawing near and listening.”

Growing up as a White boy in the South I definitely saw my fair share of racism. From micro-aggressions to full on calls for lynching.

Starting small, my grandmother always ate mixed nuts. I knew what cashews, pecans, and peanuts were but I had no idea what the big dark brown nuts were called. So I asked. The answer she gave me was ‘Nigger toes’. She was talking about Brazil nuts.

I also grew up with the Confederate flag everywhere. No matter where you went, you saw it. That’s why people in the South who aren’t consciously racist were surprised about how racist it actually is. You grow up seeing it everywhere and hearing about how it’s just a symbol of Southern Pride. You never learn when you’re young that Southern Pride is just White Pride.

I attended both public and private schools. At McAdory, Black culture was praised unless you were Black yourself. At Flint Hill (a Christian school, mind you) everyone there believed there was a difference in a black person and an n-word (usually spelled with a hard r).

Later in life I got jobs and every time, someone would ask me ‘Are you comfortable working there?’ Or if I was thinking about applying somewhere they’d say ‘Now you know a lot of Blacks work there.’ These statements would come from friends and family as though it was something EVERYONE in the South thought.

My ex was a ‘supporter’ of Black culture when it was convenient for him. He would watch Madea movies; claim The Color Purple was his favorite movie; [listen to] Black artists like Lil Wayne, Gorilla Zoe and T.I.; and thought that Beyonce was ‘pretty for a Black woman’. However, behind closed doors, saying the n-word seemed to have been as important to him as breathing. He probably learned that from his grandfather, who would throw it around like no one’s business. Or maybe his dad, who could tell you anything and everything about a White actor but every Black actor was ‘that nigger on tv’.

His mom was just as guilty. An accident caused his brother's death and afterwards, she took it upon herself to start an ‘anti-bullying campaign’ because in life he was bullied for his stuttering. This was nothing more than a guise for her to seem like she cared. If a Black person cut her off in traffic she would still scream and call them the n-word. She didn’t care about anyone of color. Only her narrow view of who should receive help.”

—Bradley Ray

I remember it being vastly different just because of the things that people said to one another. Never in my entire life up until this point had I heard some of these beliefs that people had or the things that they would say. ‘And with regard to the Civil War... also known as the War of Northern Aggression…' That was my high school American Studies teacher. I was stunned. ‘Excuse me... what is the War of Northern Aggression?’ I was always the bold one in my school. The Black, gay, atheist (at the time) liberal who would question every single thing.

“White people’s number one freedom, in the United States of America, is the freedom to be totally ignorant of those who are other than White. We don’t have to learn about those who are other than White. And our number two freedom is the freedom to deny that we’re ignorant.”

My teacher would explain that the reason it was sometimes called that because the North was not necessarily the ‘good guys’ and that they were trying to take certain rights away from the states. I guess we can guess what types of rights she was talking about.

I was an average kid in high school -- had friends, but also had enemies. There was a kid in school who would verbally attack me everyday for being gay and would sometimes slip out a racial slur alongside it. Well, one day, he hit my head with a book. I was terrified and ran away to the counselor's office. I had to meet with the counselor and the assistant principal. ‘Well, did you say/do anything to make him say/do that?’ My fucking experience in high school in the fucking South, I tell ya. It's always the victim's fault.

I tried to excel as best as I could in school because I wanted to better myself. I would always be told things from teachers that I was ‘so eloquent’ and so ‘well-behaved’ or from ‘such good stock’ -- which I always thought were such strange things to say to describe a young Black man.

My name is DeQuincy (pronounced Dee-Quincy) Deshawn Hall. I was actually named after the place that my dad was born in Louisiana, but I was always referred to as Quincy growing up. A couple of my asshole fraternity brothers would make fun of my name when I was in college. And currently, I have coworkers who will sometimes jokingly call out my full name and pronounce it: Duh-Kwincy Duh-Shawn Duh-Hall (extra emphasis on the ‘Duh’). It's as if they automatically label me because of my name or think that it's such a funny thing. ”

—Quincy Hall

named John, who was mutual friends with some other people I knew. Fast forward into our friendship and I started going to church with them. During this time, I did not have a car, so he would pick me up and I would ride with him to a church in Hoover. After the church service I would usually go over to their house and eat lunch before I went about the rest of my day. Over the course of doing this I met the whole family. I met his mother, father, brother and two sisters. They are lovely people, but I had an unfortunate interaction with his father that none of them know about. This day made me very uncomfortable.

During one of the after-church lunches, I noticed that there were more guests invited this time. Some of their other family members and members from the church came. At one moment of the gathering, I was sitting at a table with an African (I forgot his actual country of origin) man and a Nicaraguan woman. We three were the only non-White people in this house and I guess it's natural we all came together in this predominantly White space.

While sitting at the table, John's father comes over and starts taking to us and he proceeds to tell us this story about when he went to Panama. While visiting Panama, the locals told them ‘Your family is very pale. You have no color’. He laughed and then he looked at our table and said "I guess you all are my colored table" in reference to the preceding story. I could not believe what I heard. When he initially told the ‘joke’, I nervously laughed on the outside but I was feeling so uncomfortable on the inside. The Nicaraguan woman was laughing as well but her laughter seemed authentic, as if she truly thought the joke was funny. I, on the other hand, was super nervous and uncomfortable.

After that event, I went outside to sit by myself because I did not want to be around anybody. I was deeply bothered by the term ‘Colored’ because it reminded me of the Jim Crow era with the ‘Whites only’ and ‘Colored only’ signs. I didn't feel like a guest anymore, I just felt like an ‘other’.

I wanted to speak up, but I felt so powerless at that time. I felt I couldn't say anything because they invited me to their house, gave me a ride and fed me for lunch. I knew the power dynamics of the situation I was in, so I just internalized the pain I felt and I persevered through the rest of the lunch.”

—Artemus Hill

“…he would look me

up and down, his expression approving, like he was examining a fine colt, or a pedigreed pup…What I am trying to say is that it just never dawned upon them that I could understand, that I wasn’t a pet, but a human being. They didn’t give me credit for having the same sensitivity, intellect and understanding that they would have been ready and willing to recognize in a White boy in my position.

But it has historically been the case with White people, in their regard for Black people, that even though we might be with them, we weren’t considered of them. Even though they appeared to have opened the door, it was still closed. Thus they never did really see me.”

—Malcolm X

—Matt Suddarth

Before the moment described below, I had rarely heard of police racism and never seen the cultural effects of this racism. This is my story of exposure to the horror of police in America:

One time I was driving with my friend X who was seated in the passenger seat. As we drove along a warm, country road in Alabama, we talked about college classes, roommate troubles and college life. By this time, X and I were good friends, so our conversation was casual and expressive. As I passed a police officer, who was parked in a small grocery store parking lot adjacent to the highway, I noticed X suddenly became quiet and sat stiffly.

I became concerned and asked him if he was ok. He quietly said he was fine, that we had just passed a cop. I expressed my confusion because to me, policemen were society’s helpers. He then explained that he is afraid of the police because if I (a White lady) had not been driving, or been in the car, he could have been targeted because of his skin color. He explained that he was taught, from a young age, to be weary of police for this reason.

I was in complete shock. I had never heard of such a lesson. And when I returned to my dorm room I began to google ‘police racism’. To my shock, I found hundreds of cases in the U.S. in which White cops profiled, arrested and harmed Black men and women because of the color of their skin. This one experience with my friend opened my eyes to the reality that in America, not everyone is free and equal. Since then, I have called out racism in friends and family, and I have supported causes that help bring justice to black men and women who were unfairly targeted.”

—Anonymous

not to be confused with the casual racism like ‘Oh, you talk white’ or ‘You're cute for a black guy’—I was 16 and it was my junior year in high school.

I always had trouble committing to a friend group because I felt only hanging out with a specific clique was boring and lame. So I had hood friends and skater friends and nerd friends and jock friends. Even though I was an honorary member in all of these groups, occasionally there would be someone who would treat me differently because they felt I wasn't one of them. The most betraying part of this story is that it happened to me in the group of kids I felt most at home with: the band kids.

I had been in marching band since junior high and I had an exceptional bond with these people simply because we had gone through so much together. I had one friend in particular who I hung out with all the time. We shared similar tastes of music and senses of humor and I felt he was someone who would have my back no matter what.

Anyways...

We were in a rehearsal for some ensemble—I don't even remember which one—but the band director said something along the lines of everyone go to 'N’ (because music measures are sometimes labeled with letters). And people started in the wrong place because some of us though he said ‘M’. So the director cut the music and emphasized ’N’ not ‘M’. And randomly, out of the blue, my friend who I thought was my A1 says ‘So N as in Cash?!’ And everyone was like what the hell?

I remember the band director being in shock because this was, like, his most prized student. He couldn't believe he would say that but also he was waiting for my reaction because he didn't know what I was about to do…..

I'll never forget that. This wasn't the 60's. The feeling of embarrassment and betrayal was so heavy, I just left the room.” (Story 1)

there have always been places I was told not to go. I was always told that Sand Mountain was not welcoming to Black people and going there is only asking for trouble. Of course me being young and full of adrenaline and bravado, I wanted to go see what the big deal was.

I remember my friend Dobby asking me if I wanted to go to a party on the Mountain, and I was like no. I was taught specifically never to go to a party on the Mountain. But of course I secretly wanted to see what was up, so it didn't take much convincing for me to give in.

So here we are at some trailer in Powell, AL. Which has a population of 18, 17 of which were in this trailer. Keep in mind I'm with my Caucasian friends Dobby and Caleb, who I grew up with in Scottsboro.

I immediately got an awful, unwelcoming vibe from these people at this party. My nigga senses were tingling like ‘Yo, you're in danger…’

I saw the host of the party—some lady who was about 5 feet tall but, for some reason, was very intimidating—whisper something to these cornbread-fed mountain dudes and then they like went back into some room. I'm kind of posted up in a corner being anti-social at this point.

The dudes come out of the room holding two of the most beautiful dogs I have ever seen in my life. One was a red-nosed pit with black stripes and the other was a blue pit that was absolutely massive. So the dudes kind of motioned for the dogs to go in my direction. So I'm like finally this party is getting started.

I start petting the dogs. I'm amazed at these dogs. I'm a whole nigga, I don't know why they thought I would be afraid of pit bulls…..but anyways it was at that moment I realized their intention. And I saw them getting red and blue in the face when they saw I was handling the beasts quite well. It was at that point that I decided to just go outside and stand on the porch and wait for my friends.

A few minutes later, Dobby comes out and ask me what's wrong and why I'm not being myself. I didn't really even know how to explain it, so I just said we'll talk about it later. But before I could even finish my sentence the host of the party, that same 5 foot woman full of fire, comes out to the porch and says ‘I don't like niggers and I don't want ‘em no where 'round me. Niggers ain’t good for nothin’ and I don't wanna be soshated wit ‘em. There ain't nothin I can't stand more than fucking niggers.’ And blah blah blah.

So at this point I'm rolling my eyes and I'm realizing that I'm on her property. There’s three of us and like 19 of them (plus the two pit bulls). So I simply asked ‘Ma'am, where does your property line stop?’ And she pointed. And I proceeded to walk on the other side of her property and calmly waited. I knew they were trying to provoke me to anger so they could basically justify a lynching.

The only problem with all of this is my friend Caleb, who will fight a wild bear for fun sober, has consumed a surplus amount of moonshine and he's hearing the tail end of all of this. Caleb is only 90 pounds soaking wet. He tried to fight every single person in that trailer after he found out how they were treating me. Me and Dobby had to drag him out of that place.

Shout out to Caleb Hardy.

White people, be a Caleb.” (Story 2)

Even though my mom damn near disowned me for going there, I wasn't ready to go to a university so that's the route I went. And it was only 25 minutes from where I lived.

I remember when I first got my Pell Grant. I went to the bank that was right across the street from the campus to cash it. I didn't want to drive all the way to Scottsboro to my bank to deposit it because, at the time, I had moved to Fort Payne which is on the opposite side of the mountain. I decided I wanted to keep some of the money, but not in Benjamin Franklin's. I wanted some $20 bills for about three or four hundred dollars. So I waited until the next day and asked the lady at the same bank I was at before if I could have twenties instead of hundreds.

The lady has taken her reading glasses and put them on, examining the numbers on the bills.

She says ‘These numbers are in order.’

I say again ‘Ma'am I need twenties for these hundreds, please.’

She's still studying the bills. I'm thinking maybe they've had some issues with counterfeit recently so I'm not even tripping.

Then she says ‘Did you get these out of an ATM?’

And I'm like ‘WUT?’

‘Ma'am, all I need is change.’

And then she says ‘How did you get this money?’

At this point I'm in absolute rage.

I'm like ‘Ma'am, what are you even talking about? All I asked you for was some $20 bills.’

And she goes on to say ‘I don’t think this is your money.’

I was at this same bank to cash my check less than 24 hours before. She was in disbelief that I, a young black man, could possibly have in my possession three hundred dollars. THREE HUNDRED DOLLARS.” (Story 3)

I get pulled over with one of my roommates who was in the passenger seat. She just so happens to be a melaninly challenged female, so I already know I'm getting a ticket.

So I get the ticket. Whatever.

Fast forward to my court date. I had a clean record and wasn't really trying to deal with a speeding ticket. So I'm talking to the DeKalb County person for...I don't even know what you call them but the people that talk to you other than the judge in hopes to resolve things. I tell the lady that I wanted to use my youthful offender for my speeding ticket. She then says ‘No, you don't want to do that. It'll just be wasted. What are you gonna do when you get caught with something serious? You're gonna wanna save your youthful offender for when you get a possession charge or paraphernalia.’

She didn't even know she was being racist. She had no idea. She thought she was helping me

Keep in mind I don't know this lady. I've never done drugs.” (Story 4)

—Granvielle “Cash” Lee

I’ve always been a ‘love everyone’ type of person. As long as you’re not a shitty person, I like you.

So when I was younger, I lived in a small community that had 2 black families and they happened to be my neighbors. So 3 people of color in my school total. Calvin and Maria were brother and sister and Gavin was an only child. We always played with them, doing dumb stuff. Well I developed a crush on Calvin and I mean a HUGE crush! I was young so I thought I’d write him a note telling him. I poured my heart out to him and then forgot the note in my pocket that day.

My mom was doing laundry and found it. To my horror she showed it to my dad. He blew up on me! He said no daughter if his would ever date a nigger. That we didn’t mix races in ‘His House’. That we couldn’t date someone of the same sex, it was all wrong. That if I ever dated a black guy or a girl, I would no longer be his daughter.

I was devastated. Here I was, crushing on this amazing, sweet, super cute guy and my own dad was telling me I couldn’t like him because if the color of his skin. I couldn’t understand why we could ride bikes and go skating and hang out with all of them but we just couldn’t like them romantically. So at that moment I realized that something was wrong with my entire family.

For years they cracked jokes about any person of color and had no problem calling them racial slurs. Fast forward 10 years and I meet my friend Siran. She’s a beautiful six foot goddess! She was and is the kindest person you could ever meet. She stayed at our house just about every day.

Well my dad got drunk and high one night and they were joking around and she smarted off to him in a playful/serious way. He said something off-color. She didn’t like it. They got into a HUGE fight and he called her the N-word. She went off! She left crying and heartbroken.

And if she wasn’t strong already, she came back the next day and her and dad talked. She said what she needed to say about how hurt she was and why what he said hurt her. I couldn’t tell you exactly what was said but since that day my dad hasn’t muttered another racial slur. A few years ago my sister started dating a woman of color and just when I thought my dad would lose his mind, he hugged her and welcomed her like a member of the family.

My only regret is that I never stood up to parents for being the way they were. They were addicts, both of them. So I was forced to take care of my siblings. I was just afraid of what would happen to them if I decided to do something that would get me disowned.

So because of my family, I decided to NOT be like them. I wouldn’t judge anyone based on the color of their skin, I would make my decisions based how they treated others. After what happened with George Floyd, my kids started taking about the riots and how he was killed. I had to sit them down and have a very long talk with them about how we had to be better than how I was raised. Obviously they were upset about what they had been hearing and watching. Since I can never relate or know how any of it feels, I had to make sure they knew the outrage that everyone was feeling. So I had the conversation with them that my family never had with me.

In order the see a difference in how people are treated, we had to be the change we want to see.”

—Holly Holiday

The hate spiral: How your identity makes the world a worse place

“People who are exceptionally tribal in their social views and in their politics project their pain into an identity, valuing the supremacy of their subjectivity and its experience. But in the process of doing so, they negate the pain and the subjectivity of people on the other side who are essentially doing the same thing.”

If you don’t believe people of color when they tell you racism is a rampant and real thing, let me share my perspective as a White woman growing up in the South.

I had the privilege of growing up in an interracial family, meaning I’ve always been a little extra sensitive to racism. With that being said, I haven’t always been a perfect ally or said the right things. No one has. We all have biases and prejudices that we are (hopefully) correcting one step at a time.

But when you’re White on the outside, you get to observe a LOT of things that wouldn’t be said or done in mixed company, regardless of your upbringing or background.

Let me tell you about some things that have happened to me in a society so many want to claim as post-racial.

Image x Mary Catherine Fehr

1. Once, I had a cop pull me over for no reason at all. It was late, my boyfriend had been drinking heavily, yet his first question when I rolled down my window was ‘Who does this car belong to?’ He was surprised to see a lily White young woman sitting in the driver seat when the car was clearly registered to someone with a Hispanic last name. I was 21.

I admitted I had a beer before we left the party, but was in no way inebriated. Without checking my insurance or breathalyzing me, he let me go. Three miles down the road, my Black friend was pulled over and given a DUI despite the fact that he passed a field sobriety test and a breathalyzer. He spent years working to get his license back.

2. I had a friend whose parents, who claimed not to be racist, actually turned down pictures of their child in the house after they found out she was dating a Black boy.

3. I’ve seen a White guy call 18 and 19-year-olds the N-word while at a football watch party for dropping the ball. Fun fact: he’s now a police officer.

4. I’ve had people tell me they couldn’t spend the night at my house growing up because my father is Hispanic, so we probably had 10-15 people living in our home. They never asked. Their parents just assumed we lived that way because of the color of my father’s skin.

5. I dated a guy who, when people started making racial jokes around me, would quickly interject and say, ‘Well, you know, Katie’s stepfather is Hispanic, but he’s one of the good ones.’ I guess in a way he thought he was protecting me from embarrassment over my dirty dad, but the only embarrassment I felt was for staying silent.

6. I have a friend from the Midwest who used to come to parties in my hometown with me in college. Once, she called cigarettes ‘squares’ and one of the guys looked her straight in the eyes and asked if she was an N-word.

7. Once, I got behind a girl I grew up with driving home from work. She was obviously inebriated and swerving all over the road. As I pulled into my driveway after driving behind her for several miles, she stopped her car in the road and called us Sand N-words. I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. She didn’t even use the correct racial slur.

8. I grew up with girls who dated Black guys in high school and then lied to their White husbands about it in shame.

9. My own extended family jokingly called my siblings half-breeds until they were old enough to understand what it meant.

10. My all time least favorite: I’ve had friends (thank God this is past tense) who will actively use the N-word to refer to people they don’t like and then explain there is a difference between ‘those’ and Black people.

I could easily add 20 more entries to this list. I’m still social media friends with several of the people referred to here. I don’t say this to condemn them, because I do believe we all have done things when we were younger that we’ve learned from and I pray the people in every single one of these instances have done the work to overcome the virus that is racism.

But trust me when i say it is deeply interwoven into our society. When I hear you say, ‘I’m not a racist, but...’, just remember…I know because I was there. I hope you’ve changed. I know I have. Either way I’ll continue to pray for you to change your heart AND your behavior.”

— Kaitlin Bitz Candelaria

why is white christianity always adjacent to white supremacy?

and honestly, I’ve been overthinking so I’m just going to start talking. So bear with me.

The summer before I started the 6th grade, I attended Hollinger’s Island Boys’ & Girls’ Club. There was a caucasian girl that had shown me a little affection and honestly, I somewhat liked her, too. One day as we played a game in the gym, I lost the game and ended up having to clean the gym by myself. Once I finished, I met up with my class and there she was with open arms. For some reason music was playing and we danced.

Later on that day as we were chilling together, she told me ‘I’d really love to date you, but I don’t think my dad would let me date niggers.’ It took me two years to realize this girl had called me a nigger to my face and I didn’t even hear her. I was halfway paying attention, but honestly I probably didn’t want to hear it.

I probably wanted to believe I lived in a perfect world where I wouldn’t be called a nigger. Where I wouldn’t witness White women go out of their way to walk to the other side of the road just to get away from me and my friend. Have you ever witnessed a woman clutch her bag close to her because she feared you may rob her? ....Probably not.”

— Mercellous Lambert

It was a few years ago (2017) at a boutique in Mobile, Alabama. I went in with two of my White friends and we were politely greeted by the store clerk (a young White woman) and were told to ask for help if we need it, etc. We bought some items and left the store with no problems.

The very next day I went to the same exact store with two of my Black friends. The same worker was there and she did not greet us or ask if we needed any help finding things. Instead, she followed us around the store, pretending to stock items. All the while, she was just following and watching. I turned around and just stared at her for a couple of seconds until she walked away.

I was speechless, I didn’t know what to say. I asked my two friends if this happened to them often. They said yes. I realized right then and there that I had never in my life been followed by a store clerk because they thought I would steal, but for my two friends this was a common experience. How could I not recognize White privilege right in front of my face? I was presented with a side by side comparison (two-day comparison, if you will) of what it’s like to be White while shopping in a store versus being Black while shopping in a store.”

— Tabby Terry

or heard or learned as a child that are the definitions of racist. I'm a pretty, little White girl. When I got caught in the car with pot by a cop, I got let go. When cops got called on us for breaking into a pool and drinking underage, all I had to do was pour out my drink. When I got pulled over for going 105 on the interstate, he changed the number to 99 and gave me a ticket and told me to be careful on the rest of the trip.

I will never know the feeling of fear like my Black friends.

The first time I experienced racism first hand, I was in middle school and my mom and I were in a nice truck that was owned by the Black guy she was seeing at the time. We got pulled over and the police officer approached my mom and I and made us look him in the eye and tell him we were okay before letting us go.

I could only imagine what the guy in the driver’s seat was feeling.

But that really wasn’t the FIRST time I experienced racism, was it? If it had been, then I wouldn’t know that my mom was only dating that guy ‘To see what dating a Black guy was like’. And I wouldn’t have thought it was so weird because I was told my whole life I wasn’t allowed to bring home a Black dude.

My mom used to tell a story—with some kind of twisted pride—about how when I was in elementary school, I came home and thought Black people smelled weird and that is how she knew I wouldn’t date a Black person.

“White people always associated watermelons with Negroes, and they sometimes called Negroes ‘coons’ among all the other names, and so stealing watermelons became ‘cooning’ to them. If white boys were doing it, it implied they were only acting like Negroes. Whites have always hidden or justified all of the guilts they could by ridiculing or blaming Negroes.”

I basically grew up White trash. The adults around me were poverty-ridden meth heads, drug dealers and all over gross, bad people. We couldn’t keep a roof over our heads and bounced from couch to couch a lot. However, they all still thought they were better than the POC around us.

‘Nigger’ was used as everyday language. Even worse than that, I understood what ‘porch monkey’ meant in elementary school. I wasn’t allowed to go swimming in the pool when there were ‘too many Nigglets around’. So many of those things are still prevalent today, whether you want to believe it or not.

I really think my saving grace was going to Dunbar [Creative and Performing Arts Magnet School] and being surrounded by so many different people whom I have watched grow up into these amazing people and overcome all these challenges. But I wasn’t suddenly fixed of all the problems I grew up around. I had Black friends—friends I am still in contact with today—and how many did I call an oreo or ‘friend zone’ because of deep-seated things I didn’t even realize were there?

There are no words to utter to apologize for those instances, but I can be a voice now. I can protest, I can vote. I can make sure that the people I am raising will only be reared to always be a voice for injustice.”

—Jordan Elise Padgett

Los Angeles, California at the height of the Summer of Protests, 2020; Video x Ron Kurokawa

We visited Montgomery, Alabama and you would’ve thought we murdered everyone’s cat based off the stare downs we got.

2. My husband walked into a gas station in middle-of-nowhere Kentucky. He accidentally startled the gas station attendant by asking where the restroom was. When he came back out and went to pay for his snacks, she told him that when she first saw him she was frightened and didn’t know if he was there ‘to rob the place or what’. I wasn’t inside during the conversation and he didn’t tell me about it until half an hour down the road. I was FURIOUS. No one would’ve ever said anything like that to me... but he shrugged it off because things like that happen as part of his daily life. To this day he doesn’t even remember that specific incident because those occurrences are so common.

3. My husband’s family lives in northern Alabama. After we had been dating a few months, we took a road trip for Thanksgiving where I would meet them for the first time. He was driving my car. About an hour out, we got pulled over for supposedly not stopping completely at a stop sign. I thought that was weird because we had stopped and I’ve never been pulled over for anything other than speeding or having a light out.

He seemed nervous, but we left with a verbal warning. We got stopped AGAIN ten minutes from his family’s house for not using turn signals when he definitely had used a turn signal. The cop asked if we had any drugs or weapons in the car (super weird, again, never had that happen). He said no, but I piped up that it was my car and I had a registered firearm in the trunk. He asked to see it and I obliged.

Meanwhile as we were standing by my trunk he asked a lot of questions. Where had I met my husband? Where were we going? Where were coming from? Did I know the people I was going to visit? Which neighborhood? And concluded by telling me to be careful because people can’t choose who is in their family. I knew racism wasn’t dead before, but I had never witnessed it firsthand in such a blatant fashion until that day.”

—Kristina Gardner

who played football and I was attending one of his games. A mother of a White student and player sitting next to me asked me how my parents felt about my boyfriend. Due to my youth and naïveté, I didn't know what she meant. She very quietly whispered ‘Ya know, cause he's Black…’ I was so confused. I was just a young girl who liked a boy. I wasn't raised to not like someone or not be friends with someone because of the color of their skin.

I have experienced other racist comments as an adult who has dated a Black man. My most prominent instance was being told a White man would never ‘stick his dick in that after a Black man has’.”

—Sarah Jean Champion

We were both students at Xavier University of Louisiana. He came to Mobile with me for an extended weekend break from school. While we were there, we went to the flea market which was nearby my Nana’s house. We were young (he was 17, I was 18) and neither of us had cars yet, so we walked. We had that classic flea market corn during our visit. As we embarked on the walk home (~10 minute walk), we were walking along the grass on Schillinger Road towards Tanner Williams Road, where we had to turn.

All of a sudden, a white truck coming down Schillinger from the direction of Ziegler Boulevard slowed down. The truck was full of White guys. They waved the confederate flag out of the window, honked the horn repeatedly and screamed racial slurs at us. They called him the n-word and me a n-word lover. It was devastating, hurtful and made me ashamed of where I was from. I could see the visible hurt and anger on his face. I felt powerless and I’m sure he did in that moment too. He didn’t visit Mobile again for the remainder of our relationship.

The summer following freshman year, I still had the same boyfriend. One day, my great uncle came to visit at my grandmother’s house, whom I lived with. He has always been willfully ignorant and full of entirely too much hubris—it’s known amongst my family that that’s just how he is. And they often allow it or do not effectively disarm him. Prior to this experience, he made comments about former President Barack Obama’s mother being an ‘African slut who slept with many men in Africa’ and perpetuated the birther theory about Obama’s legitimate citizenship. He was also known for calling his niece, who is biracial and has a Mexican father, a wetback. He also called me a dyke when I cut my hair off the following year.

When he came over that day, he asked me to go for a ride with him to pick up paperwork related to his work. He works as a re-po man. I didn’t want to go, but I felt rude saying no, especially since he had done lot of errands for my grandmother since I had left for college. I was younger and naively nicer then, lol. Anywho, we’re riding in his truck and he says, ‘I heard you have a boyfriend at college.’ I said ‘Yes, I do, his name is X.’ He then proceeded to say, ‘He’s Black, isn’t he?’ I said, ‘Yes, he is. So what?’ Then he said, ‘Well don’t you know that n-words are for lynching, not dating?’ I exploded with shock and anger. I drilled into him, calling him a racist and went on a historical rant about the evil of racism, etc. He pulled into the place near my home, got the paperwork and then we returned. I don’t speak to him at all and haven’t for years.

The Black man I dated, who hails from Chicago, is soon entering his residency as a family medicine doctor. He is choosing to be matched with a residency in the Southern region of the US.

I have many stories because I’ve spent most of my life around Black Americans and/or Hispanic Americans. But these were the most overt and hurtful experiences I have personally had as a result of racism. I thank you again for the work you’re doing—it is so important.

Silence is Violence.”

—Victoria Taylor

at the time. It was only supposed to be a five-hour drive so I went. I had no idea where I was going so I used my GPS. Long story short, the GPS took me to the wrong house in the wrong part of town and I was losing signal because it was the country. I pulled up to what I thought was his house. Got my phone to call him and my battery life was literally two percent.

It was dark as fuck by the time I made it there. My signal was gone and I couldn't get my boyfriend on the phone. But I kept seeing this old White man watching me from his window across the street. But I'm thinking ‘Ok, well my boyfriend will see me out here soon’. Anyway, the man came to my car with a shotgun saying I must be trying to buy drugs.

Out of nowhere, I got a signal. And my boyfriend was on the phone asking where I was because he didn't see me outside (I was at the wrong house). I told him I didn’t know and told him about the man. He panicked and asked me what I saw around me, so I told him some white building up the street. He had me drive there. He rushed to me and had me follow him to his house. When we got there we both got out of our cars and he hugged me so tight and told me I went on the racist side of the hill and to never make that mistake again. To never go down that hill.”

—Erika Williams

when my parents decided we would go to school in another district: Hueytown, Alabama. I was attending Pittman Middle School, now known as Hueytown Middle. I'm not sure exactly what triggered the little boy or what I did, but we were walking to lunch and he turned around and said ‘Don't make me call you what they use to call Black people back on the farm’. Before I knew it, I had him pinned against the locker and I was encouraging him to say it so that I can punch his face in. Of course, I was reprimanded and he was not. I was sent to the office and I remember being extremely upset and crying about it.

The other experience was when I was in Lakeview in downtown Birmingham. We were at Sidebar. We had gotten drinks but we were having trouble getting through the crowd. I was with a few friends (ALL Black, of course). So this White guy walks up to us and says, ‘Hey are you ladies having trouble getting through the crowd?’ We laugh and say yes. He proceeds to say ‘Just follow me. I'M White, so I can get through here’. GIRL, IF THAT AIN'T HIM KNOWING HE'S PRIVILEGED, I don't know what is!

Besides being followed at stores and seeing my parents and friends get belittled and criticized because of how they look, what has happened in this country is not surprising at all.”

—Kiera Hood

It's okay if you end up not using it.

When I was little, my family lived in Knoxville, Tennessee. My dad was going to graduate school, so we moved there from Missouri. I started going to preschool because my older brother was going to school and I wanted to be like him and also go to school.

I don't remember a lot about the preschool, but I remember my best friend was a Black girl (I think her name was Kiki?). I wasn't allowed to sit with her at lunch time. The Black kids and White kids sat at different tables. I remember being (and still am) more confused about it than anything. Obviously, I would have wanted to sit with my friend and I don't remember really being close to anyone else at the school. I'm sure I was sad and I know that I never really got it. I have always thought that it was stupid.”

—Kimberly Frank

that changed me most and really woke me up to racism is one of my first experiences. I was about 10 and me and my little brother, who was eight, were walking back to my grandma’s house from the gas station down the street. We were carrying sticks because of stray dogs. She lived directly across from Carraway Hospital, so we were walking down the street around the hospital when I noticed a security/mall cop following us.

So we continue to walk for two minutes, until I get close enough to where I know my grandma could see me from the porch. So I stop and he turns on the lights on his little security cart and I asked him why was he following us.

He says ‘What you ‘boys’ doing walking over here? Trying to break stuff and steal, huh?’ I responded ‘No we just came from the gas station; you see the bags.’ And then I pulled out the candy and chips to show him. Then he continues to say ‘Mhmm y’all are just some little niggers trying to steal’ and that’s when I started to get angry.

But I kept calm and said ‘You’ve been following us ever since we got over here, so what did we break or steal? Nothing at all.’ And before he could say anything else, my grandma had walked all the way over where we were and asked ‘Why are you messing with my grandbabies?’ He responded saying “There been some break-ins at the hospital, ma’am,” and she says ‘Well that don’t got nothing to do with them. Did they break anything or steal anything, because I don’t see anything but candy? So we’re going home.’

And she takes us across the street to her house and sits us down and explained racism in more detail to us That was really one of the situations that really woke me up to how scary and real racism can be.”

—Michael Allen

We had just left Innesfree and decided to go to Nana Funks but we needed more cash. So we went to the ATM across the street. While we were waiting, a White man bumped my friend so hard that she stumbled, almost falling. She turned and yelled ‘Hey, watch where you’re going!’ And he turned back and said ‘Go back to Africa, where you came from,’ loud and in front of everyone. And then spat at her feet.

We were too shocked and stunned to say anything. The only thought I had was this is real. I knew it was real already, but this was like a confirmation. Trump is President and we were no longer safe. Well, no longer felt safe.

I was a junior chem major at UAB. I was sitting in the computer lab, knocking out some homework before I went home. A group of other chem majors come in: one had just had an interview with Columbia Medical School. So the group of three sit down and they talk about her interview. I’m trying not to listen but we were the only people in the room.

They asked her ‘Since you live in the South, what is your take on racism? How is it in the South?’ She says—as she keeps looking at me to see if I have anything to say—’I’m not quite sure. I mean I think it’s out there, but I personally haven’t experienced it so I can’t say if it’s real. Sure, there are patients and students of different colors but they have the same opportunities as us. I mean, we have a Black guy in our class,’ she says, laughing. This is the Black guy she and others call ‘The Chocolate Drop’. In a year, she will be a doctor.

I struggled with my identity for years, especially living in the South.

I remember speaking to my cousins for the first time. They are Puerto Ricans and live in South Bronx. I was happy to finally meet some family. We became friends on Facebook. February came and my first cousin went on a rant on how ‘Irish had slaves. Where’s their holiday? What’s the purpose of Black History Month? Why a whole month? What about us?’

I’m an Afro Latina. Afro Puerto Rican. My mom is Black. It was then I realized that not only am I the Southern cousin, but the Black sheep in my own family. There’s so much anti-Blackness in the Latino community.

I remember going to Miami to visit my boyfriend. We went to this Cuban spot and he went in front of me because I didn’t know what I wanted to order yet. When the waitress, a White-passing Cuban, realized we were together her mood changed. She gave us dirty looks. Acted like she was in a rush. She didn’t hand me my order, she put it on the table quickly.

It was like being Black is bad but dating someone who is Black is even worse. Neither one makes sense. I found out that Afro Mexicans don’t even have representation in their own constitution in Mexico. They are just now being heard. It’s insane. Anti-Blackness is global. Especially how they whitewash media. Kids wouldn’t even know that there are Black Colombians because the media and Hollywood try to erase them.”

—Lucilla “Lucy” Lazaro

We were on our way home one night and stopped in Chilton County [Alabama] for gas.

A couple of younger White guys were there and noticed that he was a Black guy with a White woman. They taunted and yelled racial slurs at my stepdad. We left the gas station and they followed, still yelling stuff out of the window. One of them pulled a gun and began to shoot at us. My sister and I were both in the backseat.

Thankfully no one was hurt.”

—Alanna Blair

When I was 13, I asked my (Black) father why I had never met my mother's parents. He went on to tell me that it was because when my mother asked them to meet me, they said ‘We don't want to associate with n****rs’. My mother later confirmed he was telling the truth.”

—Ryan Orso

Living in an Extended Stay hotel. Close to midnight one night my neighbor—who had made a permanent residence there—starts blasting his music, drunk, and had his door wide open. I asked the night manager to ask him to turn it down. I hear him get the call and say to the night manager, ‘I don't give a damn about those carpet-munching niggers’. I was appalled.

I called the night manager and told him I heard what the neighbor said. He brushed it off. Said that guy had been there a while and was just drunk. I just felt, I don’t know, just sad and disappointed, especially since the manager didn’t care either.”

—Taylor Stallworth

I was really good friends with a girl who was Black. Let’s call her ‘M’ for the sake of this story.

M and I were always at each other’s houses and I can remember her older sister teaching us the Bunny Hop in her den and us spending hours playing a Barbie game on her computer. For M’s birthday one year, she had a sleepover and her mom took the group of us out to the mall.

We all ended up getting rice necklaces made. You know, the little glass charms with a single grain of rice inside that has your name written on it and they fill the charm with goo to magnify the name? I was the only one at the party that was White and I didn’t know any of the other girls. They didn’t really talk to me, so I ended up sitting nearby or talking with M’s mom most of the time. I didn’t think much of it. I felt left out but figured it was because they all knew each other but not me.

Well some time after that, that same group of girls came up to me and M while we were playing on the playground at school. They asked M to go play with them and M asked me to join too. They quickly stopped there and said something along the lines of ‘No. We didn’t ask her because we don’t play with little White girls.’ And they told M that if she wanted to keep being friends with them, she shouldn’t play with ‘little White girls’ either. So she didn’t.

I remember crying on the playground because my friend wouldn’t play with me anymore because I was ‘a little White girl’. I didn’t change. I was the same person she’d always played with before. We ended up going to the same high school but never had a class together. The most that we ever reconnected was a civil smile or an occasional ‘Hi’ when we’d pass in the halls.

I don’t blame M. We were kids and kids are easily influenced by other kids. But even though it was close to 20 years ago, I still remember being completely taken off guard, hurt and confused as to why these girls that had barely ever spoken to me would refuse to play with me and take away my friend all because I’m ‘a little White girl’.”

It was in an area of town that was primarily a Black community. The majority of the time I worked there, I was the only White person on the teller line and the only White female. Other than me, there was one White, male banker at this location.

It was very normal for customers to tell me they’d rather wait for one of my Black coworkers to help them instead of me. They weren’t always direct about it, but they’d look at me and say ‘No....thanks...I’d rather wait for one of the others...’ or something to that affect. Sometimes I would be allowed to help, but would be asked if I was just helping for the day because ‘you sure don’t belong here’.

One woman came through the drive up when I was working that station and was trying to cash a check that was for a very large amount and her account had been very negative for what looked like a good while. Per our policy, we could not cash checks that were not from our bank against a negative account, especially not ones for such large amounts.

Legally, checks like the one she had sent in to me must be deposit only and the funds will release slowly as it is verified through what’s called a Reg C Hold. I kindly told the woman that I would be unable to cash but could deposit, and I listed the amounts that would become available and when. She started screaming at me to send her check back and she’d just come inside and make one of the other girls do it because she’d never had a problem with anyone else and that she will not stand to have a racist assist her. She was a middle-aged Black lady.

My manager heard this statement and stopped me before I could send the check back. I was not going to argue with her. There was no point to me. I was doing my job and would not risk losing it over her comments. My manager told me to step to the side and looked at the woman’s account and the check.

She got on the speaker and said ‘Ma’am, I have no problem sending this check back to you but don’t bother coming inside to see one of the other girls. No one here can do anything different than what the young lady that was just speaking just explained to you. I will do exactly what she just explained if you would like, but the only other thing I want to hear is a ‘yes ma’am’ or ‘no ma’am’. I will do my job, but I will not allow you to be disrespectful to my girls. You don’t know her but I do, and this girl is one of my babies just like every other girl in this building. If you wouldn’t say that to me or them, don’t dare say it to her’.

That manager has always been one of my favorites. Even when I stopped working there, we still talked and saw each other on occasions.

But that wasn’t the only time I was called out for being different than my coworkers. Old, White, country men loved to tell me that I didn’t fit there. They’d ask if I couldn’t find another location that was hiring in the ‘better’ part of town or say that I could be doing better somewhere else where I could be friends with my coworkers. Again, they didn’t know me or my coworkers.

We hung out outside of work. We vented and we asked for each other’s advice. We shared funny memes and stories in texts constantly and we always made birthdays special. When I went through an extremely nasty breakup, I wasn’t working at the bank anymore. But those girls, the ones that I ‘didn’t fit in with’, ‘could do better than’ and apparently wasn’t friends with, they all got together for a girls night and took me out to a male strip show. It was something that was not my usual style but those girls knew me and my story so well because we made the effort to constantly communicate and be friends. That was exactly what I needed at that moment.”

—Heather Paugh

at the time. It was around 2012 or 2013. I lived in downtown Tuscaloosa and I used to walk to the strip regularly, because it was only a 10 minute walk and it was good exercise.

I was trying to talk to this lady at the time that I was really into. She worked at Waffle House on the strip. This lady was bad though, and she actually showed interest in me so I was trying to see where it could go.

She worked late nights, so one Game Day night around 1:30 a.m. I decided to walk to the strip to see if she was working and maybe get some food for the free LOL. I was approaching the Waffle House, walking down this side road in between the Waffle House and a BP gas station. I saw who was working that night through the glass, saw she wasn’t working, turned around and started walking back home. Soon as I started walking back a police car flashed his lights and flagged me down. The cop asked what I was doing and where I was going.

I told him ‘I walked to Waffle House to see if my friend was working. She wasn’t so I turned around to go home.’ The cop said that I was ‘being suspicious’. I asked ‘How so?’ He said ‘It was just weird that you walked down the side road, stopped and turned around.’ This let me know that I was being watched for probably my entire walk.

I told the officer that I went to go see if my friend was working and that ‘being suspicious’ is not a crime in itself. That’s when he began to profile me, asking where I lived. To which I said Tuscaloosa (didn’t give my specific address) and that I’m a student at UA. This is when two other cops pulled up.

The cop then started taking pics of me and my tattoos. I asked him ‘Why are you profiling me?’ To which he stated ‘We have had a lot of gang activity going on’ and he just needed a database of tattoos. Soon as he said this, a car is driving like 45 mph down the road I was walking without his lights on.

The cop that was profiling me looked at his partner and said ‘Flag that car, it doesn’t have its lights on’. When the car approached the stop sign, the partner cop tells the driver of the car—that was full of White people—to turn his lights on and to be safe. I instantly said ‘Wait…that person clearly broke a traffic law and you tell him to turn his lights on, but yet I’m just walking, minding my business, and I get stoped and profiled?’ The cop asked ‘Do you want to go to jail?’ I said ‘For what?’ His response was ‘Being aggressive and disorderly’. So I was just quiet as he took his pictures of me.

Luckily my friend John, who is White, sees me and he says ‘Ian do you need a witness?’ I didn’t say anything, because I didn’t want to give him a reason to arrest me or beat me. John walks over anyway and started vouching for me, asking what is going on. John then asked if he could have their badge numbers. As soon as he said this, the cops said ‘We are done here, Mr. Brooken, have a safe night’.

John gave me a ride to my house, and I don’t know what would have happened if he had not been there at that moment.”

—Ian Brooken

ever since my move to Alabama, but there was one that always hit me differently than the others.

It was when I was 14 years old on the cross country team at Spain Park High School. I was literally the only African American on the team and one of the first ever. Black people are stereotypically known to be track runners unless they were Kenyan (which I got called quite a few times, just a side note).

I never felt accepted on the team, though I knew I could be good at the sport, so I ignored the obvious difference between myself and the others and just ran. As time went on, my White teammates started to get a bit too comfortable, making fun of my color and intelligence on a daily basis. I never let it bother me, as it was my goal not to hurt anyone or lash out (that doesn't mean I never did from time to time).

Well. The worst of the bunch was the fastest on the team, Brandon. He got to do whatever he wanted and everything he said was apparently funny to others. I came to practice one day wearing my usual running gear and my hat that was turned backwards. He said ‘I'm sorry, Jordan, but if you're on this team you're going to have to choose to be a runner or a thug’.

Everyone started laughing. The coach started laughing. I didn't speak for the rest of the day.

It was just a reminder that I was different. He made me feel like I didn't belong. This wasn't the only example from him, but for whatever reason that moment always stuck with me.

Years later—to be more specific, two years ago—he texted me to apologize ‘cause apparently my old coach had a convo with him about how he was ‘too hard’ on me. I never texted him back ‘cause to this day, I see him as a racist prick that can die for all I care.”

—Jordan Strong

Image x Kenny Cousins

are held to this day, I have MANY stories from when I was younger. The story I wanted to share is something from when I worked at the Child Study Center at the University of Montevallo.

This situation involves E (a White, 4-year-old, male-presenting student) and M (a Black, 4-y/o MPS). This situation takes place in Fall 2016/Spring 2017, when our nation was going through a major exchange in power and many of our students were allowed to watch bits and pieces of news.

All the parents of this group were college-educated people and many discussed politics in front of their pre-schooler. E and M had previous conversations about Trump and Obama; M favoring Obama as a super-human and E loving Trump because he would ‘Make America Great Again’.

One day during my shift, E and M were playing.

M: ‘E, come play superheroes with me!’

E: ‘Okay, but I want to be the good guy.’

M: ‘But you can't be the good guy. You're Trump and I'm Obama.’

Teachers stepped in and made it a teachable moment, but I tell this story to say this: our kids are watching every move we make.

Every single thing we say, every reaction to every single situation, everything. In this moment, it was powerful that two preschool boys from very different home lives had an understanding of the power skin color could and would play for our presidential candidate and how they individually saw themselves in each respective candidate.”

—Anonymous